The Real Deal Part 6 Huai Yin

It was in Huaiyin that I discovered my talent for consuming massive amounts of baijiu. Over the course of five years, I commuted from Shanghai to my destination four times annually, enduring a six to nine-hour journey each time. The excursion became among the most challenging, with only makeshift toilets along the road. I recommended steering clear of anything that could cause a prolonged trip to the toilet.

On the way, we passed through a section of Anhui province with a long stretch of roadhouses. Standing outdoors, the women worked to attract the attention of passing vehicles. To stop cars, they place big rocks on the road. The road’s potholes were so severe that they caused the side window of the van we were in to shatter. We stopped to find tape to keep it together.

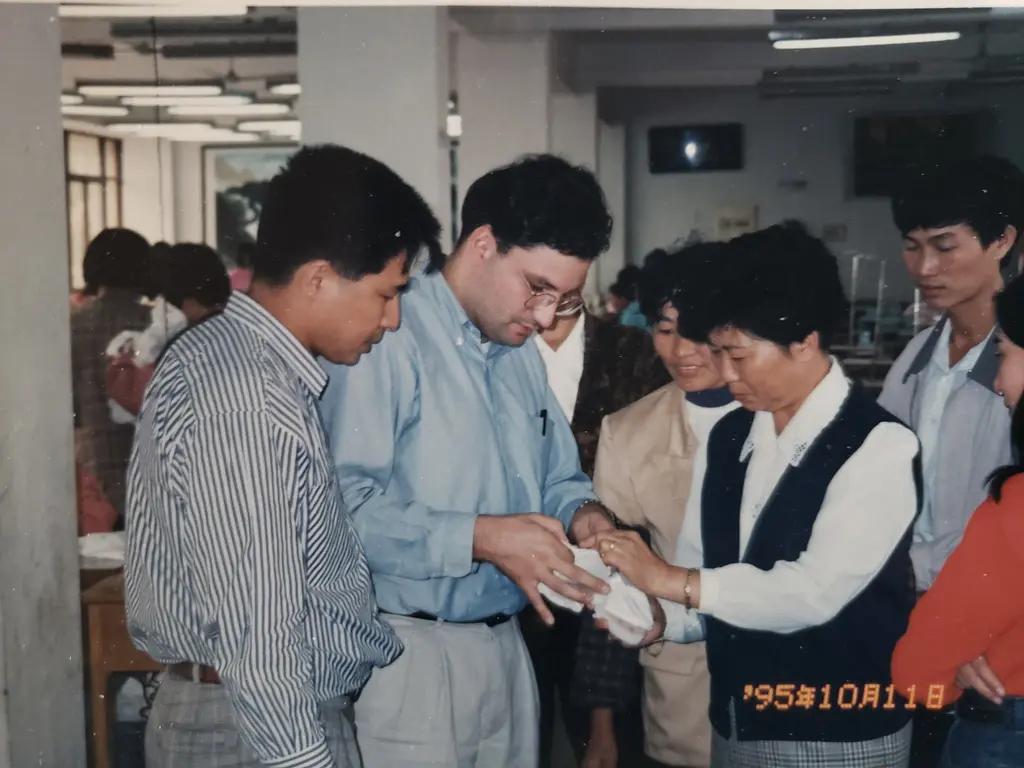

Typically, I spent the first day traveling. Since I had little interest in the town, and the banquet hall had a terrible breakfast, I spent more time exploring the factory, looking for defects. I kept myself occupied to make lunch come sooner. The factory produced basic slippers, so there was little room for criticism, but I maintained a serious attitude with a posse of managers and workers following my every move.

I rarely met other foreigners on the road, but this factory had Italian designers who visited along with a Japanese technician living in the factory. Despite being unable to speak each other’s languages, we all spoke the language of the liquor and engaged in non-stop “ganbeis” to wash away the hardships of the job. The meals in this area turned into relentless feasts, fueled by baijiu (55%) and posing a threat to the liver. With eight out of nine people at the table eager to do a four-shot toast with me, I continued drinking until everyone gave up. Meals typically lasted three or more hours. Sometimes, lunch ran into dinner.

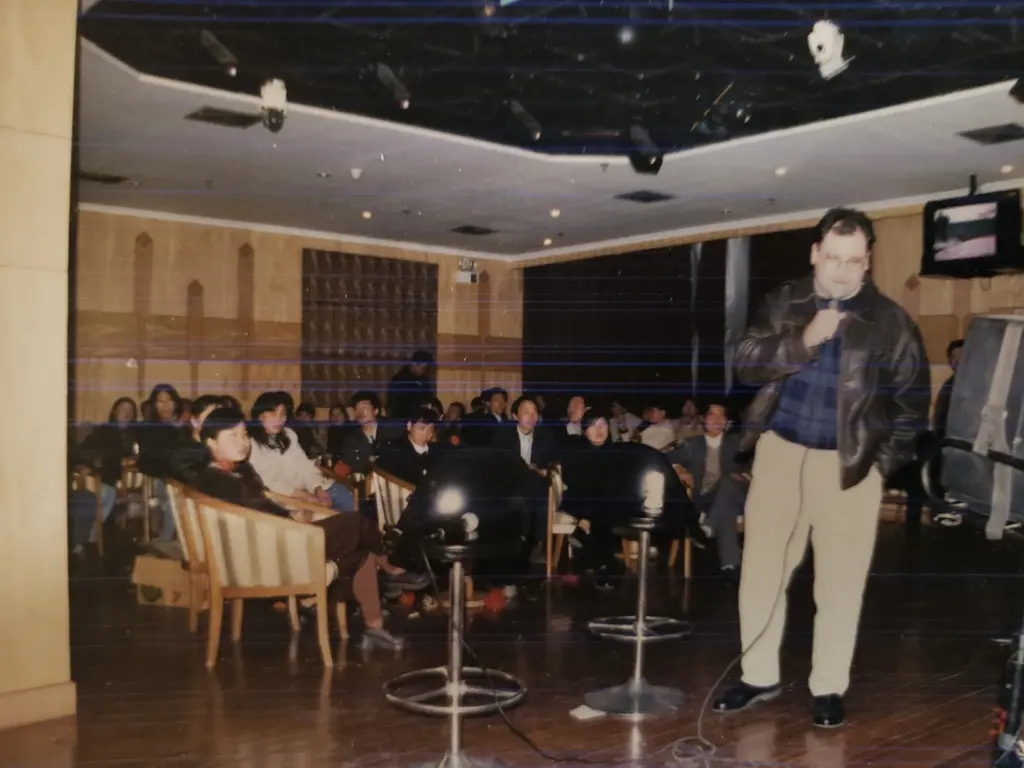

After the meals, we engaged in a late-night session of singing and dancing at the roof-top banquet hall in the factory. I was the first customer to get down with the managers and ballroom dance the night away. With no other nighttime establishments, the factory karaoke room became the best place to let the baijiu course through my veins. The managers and workers watched me play my Western music and attempt to sing along with The Doors and others while continuing to get boozed up. After I exhausted myself, they would move the chairs aside and slow dance. Meanwhile, I would venture onto the roof and see if I could get a signal for my cell phone to bug friends on the other side of the world.

Here I am singing “Country Roads” with my Japanese technician friend.

Performing for the factory.

And dancing.

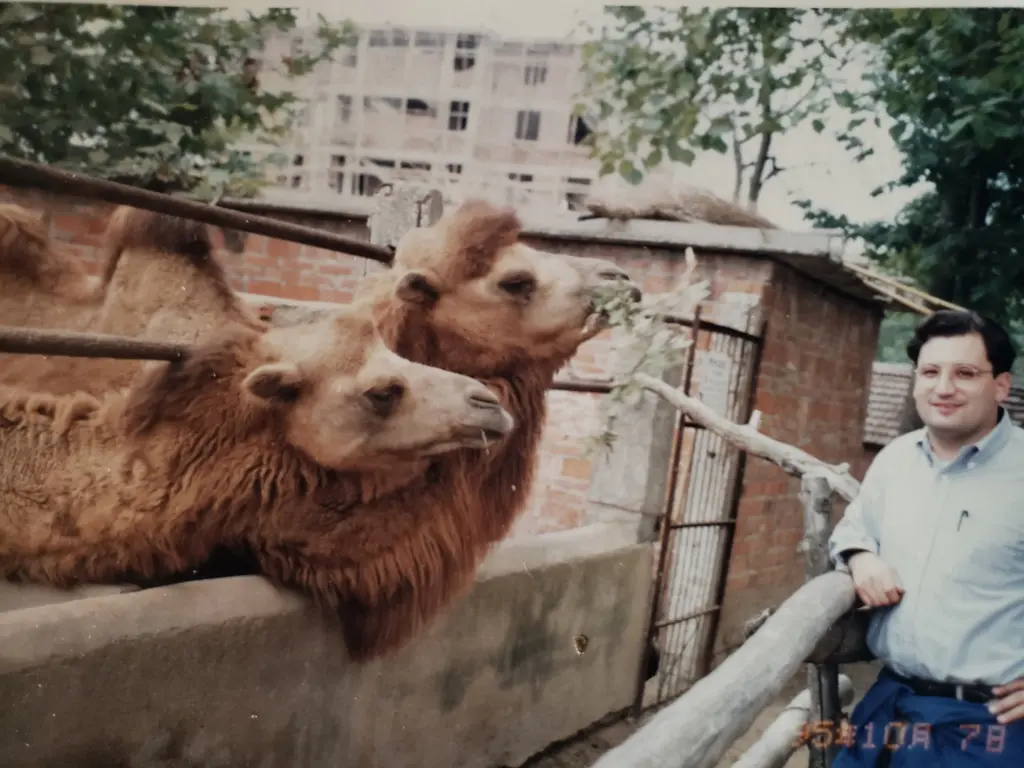

When drinking at lunch, I had to find something to do before dinner. Next door to the factory was a PLA training school. The young soldiers often shot hoops, and I joined them once with disastrous results. It was common for small towns in China to have zoos with a random assortment of animals and amusement rides. The Huaiyin Zoo was an excellent place to waste time while I walked around stinking like rocket fuel. People only noticed me because I was a foreigner, not because I was an adult riding children’s rides smelling of alcohol.

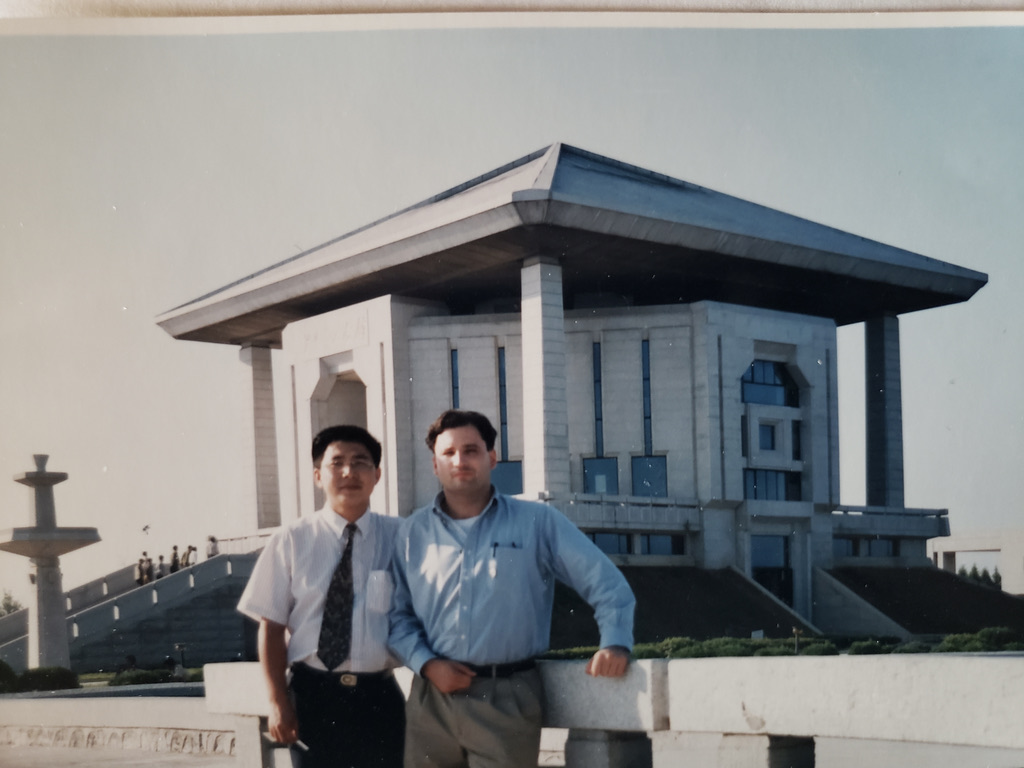

The factory organized a tour of Zhou Enlai’s home and museum for me. I learned all about the local hero.

Because of changes in the 2000s, we no longer manufactured the slippers made by the Huaiyin factories, and my other obligations prevented me from returning. My ballroom dancing days were over.